📌 After 40, these white spots appear on your arms… here’s what they really mean

Posted 3 December 2025 by: Admin

Understanding Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis: The Mystery Spots Revealed

Those small white patches that gradually appear on your arms and legs have a name: idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH). Despite its intimidating medical terminology, this condition is remarkably common and entirely harmless.

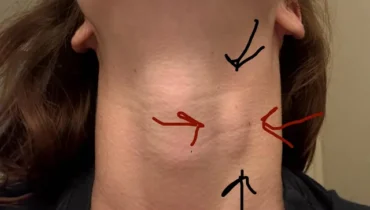

IGH manifests as flat, white spots measuring only a few millimeters across. The condition develops when melanin—the pigment responsible for skin color—diminishes or disappears completely in localized areas. These patches typically emerge on sun-exposed zones: arms, legs, and occasionally the face. They affect people across all skin tones and ethnic backgrounds with striking consistency.

The prevalence data is telling. Between 50% and 80% of people over age 40 develop at least a few of these spots, making them less an anomaly than a predictable marker of aging. Rather than signaling disease, they represent a natural progression of skin changes over time.

What makes IGH distinctive is its visual presentation. The spots remain flat and smooth, distinguishing them from other skin conditions at a glance. Their appearance becomes more noticeable as surrounding skin tans or darkens, creating sharper contrast. This visual prominence often triggers concern among those unfamiliar with the condition, yet medical literature consistently confirms its benign nature.

Understanding what these spots actually are—and what they’re not—provides the foundation for addressing them appropriately. The question shifts from whether they’re dangerous to understanding why they form and what, if anything, can be done about their appearance.

The Science Behind Sun Damage And Pigment Loss

The foundation of IGH lies in a straightforward biological process: ultraviolet radiation systematically damages the cells responsible for skin pigmentation. This isn’t a sudden event but rather the cumulative consequence of years—often decades—of sun exposure.

Melanocytes, the specialized cells that produce melanin, are particularly vulnerable to UV damage. When these cells encounter repeated ultraviolet radiation, their ability to function deteriorates. Some cells die outright; others simply cease producing melanin altogether. The result is predictable: those small areas lose their color, appearing pale or white against the surrounding skin.

The mechanism unfolds in three stages. First, UV radiation penetrates the outer layers of skin, targeting melanocyte cells directly. Second, this damage accumulates over time, as each sun exposure adds to the cellular injury. Third, once enough melanocytes are destroyed in a localized area, that spot becomes permanently lighter. The process is irreversible once the damage reaches this point.

This explains why IGH correlates so strongly with age and sun exposure history. People who spent decades in sunny climates or working outdoors develop more spots than those with limited sun exposure. The arms and legs—areas frequently exposed without protection—bear the heaviest concentration of these marks.

Importantly, this isn’t a sign of sun damage in the catastrophic sense. Unlike melanoma or severe photoaging, IGH represents a specific, benign manifestation of cumulative UV exposure. The body’s response is simply to lose pigmentation in scattered spots rather than develop dangerous lesions. Understanding this distinction clarifies why dermatologists treat these spots so differently from other sun-related skin conditions.

Treatment Reality: What Works And What Doesn’t

For those bothered by these white spots, the question naturally follows: can they be reversed? The answer requires honest acknowledgment of current medical limitations. No medically proven permanent cure exists for IGH, despite the various treatments marketed online and in dermatological settings.

Several options circulate regularly: topical retinoids promise to stimulate melanin production, chemical peels attempt to resurface affected areas, and laser or light-based therapies aim to reactivate dormant melanocytes. In theory, these interventions address the underlying problem. In practice, they rarely deliver lasting results. Dermatologists remain cautious about recommending these treatments specifically for IGH because melanocyte cells, once destroyed by UV damage, cannot be reliably restored.

The fundamental problem is biological rather than technological. Once melanocyte cells have been lost, current medical science lacks the means to regenerate them permanently. The few studies examining these treatments report inconsistent outcomes—some patients see minimal improvement, others experience temporary fading that eventually returns to baseline. The unpredictability makes aggressive intervention difficult to justify for a harmless, purely cosmetic concern.

This reality distinguishes IGH from other treatable skin conditions where intervention targets active disease or genuine health risks. Here, treatment attempts address appearance alone, against odds that favor disappointment. Understanding these limitations prevents wasted resources on expensive procedures unlikely to deliver satisfying results.

The practical path forward shifts focus from cure to management and prevention—a distinction that reshapes how patients approach these persistent marks.

Distinguishing IGH From Fungal Infections And Practical Management

A common source of confusion arises when people mistake these white spots for tinea versicolor, a fungal infection that produces similar-looking patches. This misidentification often leads to ineffective treatment attempts with antifungal creams or medicated shampoos—a costly detour that yields no results because IGH is not caused by fungus.

The distinction matters. Fungal infections typically appear on the chest, back, or shoulders and may display scaly texture or accompanying itchiness. IGH spots, by contrast, manifest almost exclusively on sun-exposed areas like the legs and arms, appearing perfectly flat and smooth without irritation. If your pale patches are spreading rapidly, causing itching, or changing appearance, consulting a dermatologist remains prudent to eliminate other skin conditions.

For those accepting IGH as a permanent reality, practical solutions exist within reach. Body makeup and self-tanning products effectively even out skin tone temporarily without medical intervention. Daily sunscreen application serves a dual purpose: protecting against further UV damage while preventing additional spots from emerging. Consistent moisturizing enhances overall skin appearance and texture, addressing the broader concern of skin health rather than pursuing impossible cures.

These modest interventions acknowledge a fundamental truth: these spots are normal, harmless, and extraordinarily common as skin ages. They require no medical treatment, pose no health threat, and reflect nothing about personal hygiene or lifestyle choices. The visible marks simply testify to time spent living—a perspective that transforms these pale dots from cosmetic embarrassments into ordinary features of human aging.